What follows was written by a reader of this blog (who goes by CQ) as a comment to several posts having to do with the prospect of cruelty-free agriculture. I thought it would be missed by too many readers as a comment so I’ve chosen to post it as an official entry. Some fascinating stuff in here. Enjoy -jm

Is a vegan diet that includes grains less violent than the diet of a meat-dairy-and-egg-eater?We’ve been going ’round and ’round that question on various posts in the Eating Plants (now James-McWilliams.com) blog, haven’t we?Recently, I found someone who has been attempting to reduce the harm to animals from grain production down to zero.

Helen Atthowe of Montana is a vegan agricultural ecologist who is behind http://www.veganpermaculture.com and whose writing, photos and videos of her veganic permaculture farm are featured on it. According to Atthowe, humans who eat grain cannot, for the most part, escape causing suffering and death to other living organisms.

Consumer demand for bread, pasta, cereal, crackers and chips, Atthowe laments, has homogenized the landscape into a monoculture of annual grasses—wheat, corn (maize), rice, oats, rye, and barley grains, all called cereal grains. Even organic vegan cheesy puffs use monoculture grains. (Another monoculture crop, soybeans, is a grain legume; livestock are fed almost all the soybeans grown in the U.S.)

This vast production of grain by modern agribusiness inevitably kills many birds, small mammals, and insects. It is also hard on larger wild species, not to mention on the land itself. At present, a typical vegan eats the same grains as non-vegans simply because there are not yet any commercially viable veganic grain production systems. But thanks to the efforts of some dedicated scientists around the world, annual grains grown as single cash crops will not remain the only large-scale option much longer.

Indeed, grains can be grown and are being grown in less disruptive polyculture systems. Polyculture systems, says Atthowe, closely mimic nature’s ecosystems, within which insects, birds, small mammals and other wildlife thrive. These polyculture grains can be grown as perennials, with reduced tillage and hence less disturbance of the organisms who rely on a stable soil system.

For the past 30 years, Wes Jackson, Ph.D., president of The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, has been working on “perennial polyculture” grain production modeled on a prairie system. Jackson is one of eight scientists who authored a three-part series, “Breeding perennial grain crops,” published in the June 1, 2002, edition of Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. In part one, the authors write:

“All of our current grain crops are annuals; therefore, developing an array of new perennial grains—grasses, legumes, and others—will require a long-term commitment. Fortunately, many perennial species can be hybridized with related annual crops, allowing us to incorporate genes of domestication much more quickly than did our ancestors who first selected the genes. Some grain crops—including rye, rice, and sorghum—can be hybridized with close perennial relatives to establish new gene pools. Others, such as wheat, oat, maize, soybean, and sunflower, must be hybridized with more distantly related perennial species and genera. Finally, some perennial species with relatively high grain yields—intermediate wheatgrass, wildrye, lymegrass, eastern gamagrass, Indian ricegrass, Illinois bundleflower, Maximilian sunflower, and probably others—are candidates for direct domestication without interspecific hybridization. To ensure diversity in the field and foster further genetic improvement, breeders will need to develop deep gene pools for each crop. Discussions of breeding strategies for perennial grains have concentrated on allocation of photosynthetic resources between seeds and vegetative structures. But perennials will likely be grown in more diverse agro-ecosystems and require arrays of traits very different from those usually addressed by breeders of annuals. The only way to address concerns about the feasibility of perennial grains is to carry out breeding programs with adequate resources on a sufficient time scale. A massive program for breeding perennial grains could be funded by diversion of a relatively small fraction of the world’s agricultural research budget.” (Go to http://www.landinstitute.org and click the dropdown menu Publications/Science.)

Another type of perennial polyculture, forest farming, is being practiced by New Forest Farm in Richland County, Wisconsin. The 100-acre property has been converted from annual monoculture crops (commodity corn and soybeans) to a “food forest” growing fruits, nuts, berries, asparagus and other woody perennials. Although New Forest Farm grows some annual grains (wheat, rye, barley), they are inter-planted within the tree crops. [For a look at a 2,000 year old oasis food forest found in the Morocco desert, see http://www.ecofilms.com.au/2009/10/13/2000-year-old-food-forest-in-morocco. Other films on food forest permaculture are here:http://www.ecofilms.com.au/category/permaculture/food-forests

Then there are perennial wheat breeding experiments. They began in the early 1900’s, when USDA scientists began making crosses. Since then, scientists from the USSR, the University of California, Montana State University, and the Rodale Institute have worked with perennial wheat. For many years, none of these efforts could compete economically with annual wheat production. First-year yields of perennial wheat reached 70%-to-80% of annual wheat, but in successive years yields declined. More recently, however, some promising work on competitive perennial wheat has been done by the aforementioned Land Institute as well as by Washington State University (WSU) and Michigan State University (MSU).

At WSU, for example, Stephen Jones is currently testing several varieties of better-yielding perennial wheat. These plants live between two and five years, producing a seed crop each summer. This seed contains more protein and more micro-nutrients than annual wheat, and its quality is similar to that of annual wheat. In some cases, unfertilized perennial wheat yields have been reported to be equal in some instances to soft white annual winter wheat, harvesting 20 to 35 bushels per acre.

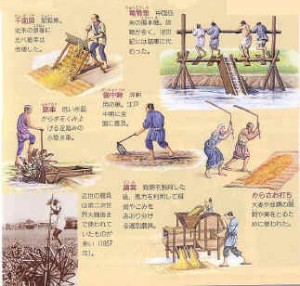

Rice is another candidate for perennialism. From 1995 to 2001, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) developed perennial rice cultivars to reduce erosion on the steep slopes where upland rice is often grown. Plant populations from IRRI’s breeding program were distributed to cooperators in China, where perennial rice breeding efforts continue. Masanobu Fukuoka, who passed away at age 95 in 2008, grew rice in Japan with no tilling, weeding, or spraying for insects and diseases. Yoshikozu Kawaguchi grows rice in Japan with no tilling, no spraying for insects and diseases, and minimal weeding. Atthowe is working on refining Fukuoka’s methods for small-scale grain production at her farm in northeastern Montana; she reports she has had some success.

Moreover, native perennial grasses are being studied for food production. In fact, Atthowe is harvesting grain from a perennial grass called Indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides) for human food. Indian ricegrass is a native dryland prairie bunch grass. A cultivar of this native grass, Rimrock, is being produced, milled, and marketed under the trade name Montina. Yields vary between 250 and 500 kilograms per hectare, but improvement through breeding may be possible, says Atthowe. In short, Atthowe declares, “we do not have to produce grains in monoculture. We can design agro-ecosystem farms that enhance species diversity and respect wild areas and species.” Leaders in this field are the Wild Farm Alliance of California and Gary Nabhan of Arizona. Atthowe has done some work in this area, too, which she tells about on her site veganpermaculture.com.

Of course, it isn’t only monoculture grain production that kills birds, small mammals, and insects. Large-animal and small-animal producers deliberately kill “rodents” and insects in order to pass public health inspections. Predators, such as coyotes, are murdered at an alarming rate to protect the cattle, sheep, chickens, and other livestock on small farms and homestead livestock operations. Large livestock production, in particular, homogenizes native plant landscapes into permanent pastures. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2006 data, livestock production accounts for 70% of all agricultural land and 30% of the land surface of the planet.

Then there is the violence of killing the animals that become food for humans. At Animal Visuals, Mark Middleton published data in October 2009 showing that a plant-based diet kills the fewest animals. In this study of eight food categories, when one million calories of grain is produced for direct human consumption, 1.65 animals die. When the same amount of grain is produced for humans to eat the flesh of chickens, 251.1 animals die. The other two categories of food that vegans eat, fruit and vegetables, cause the deaths of 1.73 and 2.55 animals. The consumption of (dairy) milk, pork, beef, and eggs kills 4.78, 18.1, 29.0 and 92.3 animals, respectively (see http://www.animalvisuals.org/projects/data/1mc).

Until animal-friendly, economically viable grain production systems become more widely available, vegans do have choices. They can limit their intake of grains, including processed foods that contain grains. They can also grow veganic grains on their own plots of land. That’s what Robert Monie does. Retired from a local community college, Monie, a vegan who lives in New Orleans, Louisiana, has experimented with no-till and low-till approaches on a micro scale, both in his backyard gardens and in tiny, shared garden plots on land worked by Vietnamese farmers. Monie says the term vegan “does not mean total absence of animal or insect content. It means the least animal or insect content we can practically achieve.” He believes that “vegan farmers will have to be brave, because they are setting out on uncharted waters that will require great innovations to help them arrive at their destination.

“Vegan farming and a large-scale shift to vegan diets will not be business as usual,” he notes. “It will require growing methods never tried on a large scale, such as perennial grains, forest farm polycultures, and living mulch turnovers of the kind pioneered by Fukuoka and Kawaguchi in Japan, but without the chicken manure Fukuoka used. “The shift from standard farming—even of the organic kind—to vegan will be as radical as the shift from fossil fuel energy sources to renewables like photovoltaics and will probably require technical expertise of the same order that has gone into research and development in solar energy,” he adds.

It is true, admits Monie, that “no one will know the extent to which cruelty in farming grains and vegetables can be reduced until numerous vegan commercial farms have been set up to try these new methods. Farming is, above all, a practical art, so there can be no a priori answer. “Nor,” he says, “can we expect ‘tradition’ to come to our aid. Tradition—that is, cultural patterns that we’ve been indoctrinated with and that we tend to fall back on— tells us we must plow the field, manure it with animal droppings, and eat animal flesh.

“As Thoreau remarks in Walden, tradition has it that animal food is necessary to build strong bones, and yet the ox, having never heard this tradition, ignores it, eats plants, and builds stronger bones than those of any human.” So, based on the research done thus far, it appears that the question “Is a vegan diet that includes grains less violent than the diet of a meat-dairy-and-egg-eater?” can be answered “yes.”It will become a even more emphatic “yes” as polyculture perennial grains become ever more economically viable and are increasingly marketed to a public eager to minimize their footprint on the earth and improve their relations with earth’s nonhuman inhabitants.

Grains may become the ultimate harmless vegan food. Veganic cheesy puffs, here we come!

Check out the “Of Interest” section of my website and you’ll learn that Chipotle is in a bit of trouble with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The issue involves “immigration compliance.” The company, which is still coming down from its much ballyhooed “Food with Integrity” campaign, will now have to prove that they hire with integrity as well. Forget fines, criminal charges look to in the company’s future.

I’m not a fan of Chipotle. The company shamelessly greenwashes its image through clever advertising campaigns and symbolic support for local farmers. Gullible consumers choose Chipotle because they buy the hype. They think the company has opted out of the industrial food system. One of its more insidious advertisements mentions how its burritos are “food culture changing.”

The fact is, though, that Chipotle would not, could not exist without industrial agriculture. A company cannot serve tens of thousands of customers tortillas stuffed with pork, beef, goat, chicken, cheese, sour cream, and mayonnaise without being deeply involved in industrial production, distribution, and supply. So what if the company gets all its pork from Niman Ranch? Niman has had to grow, consolidate, and compromise in order to fulfill Chipotle’s demand. It’s a damn hoax, punctuated by the fact that a typical burrito has twice the calories of a Big Mac and more sodium than the overall RDA measure. Integrity.

I’d be perfectly happy if the company was busted for labor violations. If nothing else, it might be the beginning of the grand unmasking of America’s shiftiest fast food joint.

The animal rights group FARM is preparing to pay Americans across the country a dollar to observe a four-minute video of undercover factory farm and slaughterhouse footage. FARM representatives are touring the country in a large van with eight screens that allow 32 simultaneous viewings. The pay-per-view van promotes, according to Gary Smith, “an increasingly popular educational strategy employed by animal activists, in which viewing stations are set up with headphones and a privacy enclosure around each screen.” This mobile option is unprecedented, and certainly “the most audacious and ambitious campaign FARM has undertaken in their 30-plus years.” Photos of the van and the video are available at http://www.10billiontour.org/press.html.

- According to the USDA reports, nearly 10 billion land animals are killed each year for food in the US alone. The number of aquatic animals killed for food is not accurately reported but has been calculated to be even greater.

- The 10 Billion Lives public-awareness campaign is coordinated by Farm Animal Rights Move- ment (FARM) and offers incentives for people to view a four-minute video depicting the con- ditions of animals raised for food.

- The North American Tour is the most public and ambitious element of the campaign, travel- ing the country paying people $1 each to watch the video. This tactic is called “pay-per- view” and has been popular in the animal rights movement since 2010.

- Prior to the 10 Billion Lives Tour, Farm Animal Rights Movement has employed the pay-per- view tactic via laptops and flat-screen monitors at festivals and college campuses. Onsite, 80% of participants pledge to eat fewer animal products after viewing, and over 60% of re- spondents to follow-up surveys report maintaining their pledges.

- This is the first time this tactic has been conducted on a national scale. In the first year of the tour, FARM expects to reach 100,000 viewers with the pay-per-view tactic and to compel thousands of others to visit the www.10BillionLives.org website, which offers a chance to win movie tickets in after watching the video.

- The 10 Billion Lives campaign and tour support a growing US trend towards concern for ani- mals and a reduction in animal consumption. A 2003 Gallup poll demonstrates that 96% of Americans believe that animals deserve at least some legal consideration. More recent Harris polls indicate that nearly 33% of Americans deliberately eat meat-free meals at least some- times, with 5% being fully vegetarian. An even higher number of teens (7%) are vegetarian. http://www.gallup.com/poll/8461/public-lukewarm-animal-rights.aspx http://www.vrg.org/journal/vj2011issue4/vj2011issue4poll.php http://www.vrg.org/press/youth_poll_2010.php

- This momentum has in turn created the intended result of reducing the number of animals killed for food. While the numbers vary from year to year, the last decade has a seen a downward trend in animals killed for food. http://animaldeathcount.blogspot.com/2012/02/comparisons-by-year.html

- By getting commitments from 80% of 100,000 participants to eat fewer animal products, FARM estimates that 1 million fewer animals per year will be raised for food as a result of the 10 Billion Lives North American Tour.

Advocates of eating “humanely raised animals” often describe the imposed death of an animal as “just one day” in an otherwise happy life. Forget the fact that this comment embodies the absolute worst manifestation of human arrogance, an arrogance so acute it casually confers to us justification to end the life of a sentient being. Let’s take it a bit further than arrogance, though.

Push advocates of “humane killing” (the phrase just galls me) to justify the legitimacy of that “one day” argument and they’ll usually say that animals have no sense of the future and, as a result, it’s okay to end the game of life whenever a human feels like doing so. They have no idea what they’ll be missing. It goes without saying that these so called compassionate carnivores would never apply this logic to human beings, which makes them, of course, blatant speciesists, a designation no more flattering than to be called a blatant racist, sexist, or homophobe. But, again, let’s take it one step further.

Ask these “ethical butchers” to prove that the animals that they’re so mercifully killing don’t in fact have a sense of the future. Push them on this. What you will find is that they cannot support that case, primarily because it’s unsupportable. Three questions is all it takes to reveal this ignorance: Do farm animals make choices? Yes. Do they make these choices arbitrarily? No, they have some goal in mind. Does that goal exist in the past, present, or future? Future. Conclusion: farm animals do have a sense of the future, so to kill them is to deny them of a future they understand. And that’s not humane. That’s cruel.

By denying to animals their sense of the future we “bespeak a prejudice,” to quote Tom Regan, “rather than unmask one.”

Yesterday I wrote about straying from the herd, but today I’m going to kind of counter myself and advocate the wisdom of collectivity. It begins with this observation, which hit me as I was struggling to find a vegan option in a very un-vegan friendly restaurant on a very poor island in the middle of the Caribbean: for better or worse, ideas and values have the most influence on customary behavior when they’re institutionalized.

Indeed, whether organized as a church, government, non-profit, or private corporation, institutions as a rule corral similar individual beliefs, collectivize them, smooth them out, and, depending on how powerful the institution, integrate them into society in a way that makes them as powerful as they are invisible. When done “successfully,” institutions become synonymous with something like a subconscious ideology. They embody ways of thinking about life that are so commonly accepted, so quietly woven into the fabric of mental life, that the driving ideas themselves rarely (if ever) have to run for re-election.

Consider one of the most pervasively normalized habits in the developed (and developing) world-eating animals. Behavioral omnivorism might strike practitioners as part of some cosmic natural order. In fact, it’s a constructed habit that benefits from a formidable multiplicity of overlapping institutional interests. The government, the media, corporate America, and religious groups all actively promote, in one way or another, the institutionalization of animal exploitation for food we do not need, for flesh that provides pleasure, for hubristic verification of our sophistication and civility. The belief that there’s nothing morally wrong with eating animals is everywhere and, as a result, it’s nowhere (at least in terms of being held up as something we should question).

Ethical vegans direct their efforts toward reforming or, in some cases, dismantling the institutions most complicit in promoting the ethic of animal exploitation. We oppose factory farming, shame the producers of fur, and boycott the circus. We hand out leaflets, write impassioned blog posts, support vegan restaurants, picket puppy mills, and more. Most importantly, true believers that we are, we live our lives as vegans, personally eschewing as much animal exploitation as we’re able to do. This individual response to animal exploitation-ethical veganism-is obviously a prerequisite to the larger cause of ending animal exploitation. While it’s true that vegans have a tendency to be fragmented by “the narcissism of petty differences” (I wish the term was mine, but it’s Freud’s), we are more likely to set a self-effacing and charismatic example of living life deliberately, with humble compassion.

So, to my point: our individual responses may very well require institutional verification to reach the depth of subconscious ideology. Individual vegans-at some point in time, who knows when?-may have to subsume their many individualities in some sort of institutional collective in order for our vision to become not only better unified, but pervasive to the point of invisibility. And this, of course, will strike many vegans as a problem. Ethical vegans can be instinctively suspicious of institutions because institutions require bureaucracies, perpetuate the very hierarchies we’re working to overcome, and iron out so many of those petty and narcissistic differences. Institutions are seen by vegans as engines of compromise and soulless uniformity. Institutions don’t rebel.

These are serious concerns, ones that cannot be downplayed. However, we may have to live with the prospect of institutionalized veganism. We cannot-at least I don’t think we can-dismantle the preexisting institutional frameworks of animal exploitation and then expect to stand alone forever, atomized and veganized, no matter how much solidarity we might achieve as autonomous exemplars of our cause. It’s for this reason that, as vegans push our agenda into the public arena, we must also contemplate ways to institutionalize with minimal compromise, recognizing that, unlike individuals, institutions-even ones that pursue the most noble of causes- don’t have the luxury of avoiding at least some involvement with power, dependence, and hierarchy. Could it be that these very qualities-ones we so often deride as supportive of animal exploitation-are required to end that exploitation?

In any case, please comment, agree, disagree, and, if so inclined, subscribe.

I just finished reading Michael Specter’s May 14 New Yorker piece on bioengineering (see “Of Interest” on this blog). Like most of Specter’s articles, this one focused on scientists pushing the boundaries of what’s considered normal. While the topic itself might not be of interest to vegan advocates-and, indeed, while the article has nothing to say about veganism per se-it nonetheless captures a phenomenon every ethical vegan understands: the frustration of promoting unconventional ideas in a conventional world. In this respect alone, it is well worth reading. Several quotes from the article helped me in my constantly evolving effort to situate vegan advocacy in our aggressively non-vegan world.

“The idea of interfering with benign nature is ridiculous. The Bambi view of nature is totally false. Nature is violent, amoral, and nihilistic. If you look at the history of this planet, you will see cycles of creation and destruction that would offend our morality as human beings.” -Peter Eisenberger, founding director of the Earth Institute

Okay, a bit hyperbolic. But still, it’s essentially true. Eisenbeger’s assessment evokes part of what I was after in yesterday’s post about farming according to the dictates of nature, which has become a dangerous pretext for farming holistically with animals (by exploiting them). My argument, as it were, was that farming should not follow natural cycles but should, instead, make those cycles more humane and efficient through aggressive and morally aware human intervention. The appeal to the supposed superiority of nature is undermined nicely in Eisenberger’s quote. Plus, whereas behavioral omnivores frequently deploy the “nature red in tooth and claw” justification for killing animals as if quoting secular gospel, it is important to remember that the violence inherent in nature can be drawn upon much more effectively to promote a vegan agenda. In essence, this aspect of nature empowers us to end as much of that violence as we can.

“There is a strong history of the system refusing to accept something new. People say I am nuts. But it would be surprising people didn’t call me crazy. Look at the history of innovation! If people don’t call you nuts, then you are doing something wrong.”

-Eisenberger again.

Well, hell yes. This remark really hit home and fired me up. Historians (among other professionals and “experts”) are supposed to be objective, fair minded, and unemotional seekers of truth. As an historian and a thinker, however, I’ve chosen to follow my gut, and that has meant throwing flames, throwing objectivity to the wind, and, as a result of all this throwing things around as if in a tantrum, risking the loss of professional respectability (thankfully, I’m tenured). Needless to say, anyone who advocates for animal liberation in a world where animal exploitation is the status quo can identify with being perceived, in Eisenberger’s words, as nuts. So I thrilled to his claim that if people don’t see you as nuts, you need to work harder. I was also reminded of Carolyn Zaikowski’s recent and brilliant essay (re-posted here a couple of days ago). In an e-mail exchange, she noted that, “I suppose my essay is formulating a bit of a utopia in general”-in other words, nuts. But she went on to add: “I think the visions need to be raised even if they can’t be perfectly manifested.” Well, hell yes.

“Climate change is not so much a reduction in [agricultural] productivity as a redistribution. And it is one in which the poorest people on earth get hit the hardest and the rich world benefits.” -Ken Caldeira

Vegans eat in a way that would substantially help ameliorate this problem. Not only does veganism support an agricultural transition that directly and substantially reduces GHG emissions, but it also promotes a way of eating that’s more diverse, accessible, and affordable than the mono-culture-based system required to sustain the western diet. This diversity factor is especially important, as it will conceivably allow poorer regions on the world (the ones most vulnerable to the impact of climate change) to develop agricultural systems that are plant-based, climatically adaptable, and tied into regional, and even global, economies. In this sense, veganism does more than reduce the impact of climate change, but it serves human justice as well as justice for animals.

Note: For another excellent article on challenging convention (in science), see Michael Dyson’s typically wonderful and inspiring essay in the May 5 New York Review of Books (also listed in “Of Interest” on this blog)

I’ll start with two related thoughts, and then run with them. First, I’m thrilled by technology. It’s not I that I think technology will solve all our problems-I’m no determinist-but it’s just that I see technology as a vast arena of innovation, a place where humans can pour an abundance of natural creativity and, at times, reap substantial humanitarian and environmental rewards. In many ways, what makes life meaningful-what gives us pleasure and allows us to reach our potential as engaged human beings-is linked in one way or another to technological advancement. I’m well aware that technology is also the cause of immense suffering and ecological degradation. Nevertheless, there’s no disentangling humanity from technology. Systematically meddling with natural resources is, for better or worse, an important part of what defines us as a species.

Second, I’m impatient with the idea that technological advance is somehow a deviation from what’s “natural.” This is a common rhetorical strategy used by the spokespeople in the sustainable food movement to deride many agricultural technologies as artificial and destructive. It’s also a questionable pretext for insisting that we must grow plants and fatten animals according to more “natural” or-big buzzword here-”holistic” methods, drawing upon processes that occur in nature without human intervention. It’s also an intellectually lazy understanding of nature. In this formulation, nature becomes something not only falsely segregated from technology (and thus from humanity), but it becomes something that we’re supposed to think of as inherently superior to “artificial”-i.e., processes designed with human participation. Yes, the buffalo once fertilized the land that produced the grasses that fed buffalo when there were very few people around North America. That was natural, we’re told. But more people are now here. Billions more. And agriculture has to feed them. So it’s time for a new natural.

I’ll concede that my heart pulls toward the romanticized preference for natural methods. And the fact is this preference would be fine if there weren’t 7 billion people living on earth, with about two billion more on the way, and billions more on the verge of entering the middle class. But, as it now stands, to allow nature to be our farmer-which is what the sustainable food people say should happen-is to promote two of the more dangerous aspects of agriculture: systematic animal exploitation and gross inefficiency in plant production. Indeed, it’s a central tenet of the sustainable food movement that responsible and “natural” agricultural systems require the incorporation of domesticated (and thus genetically exploited) animals to enhance soil quality. Similarly, it’s a central tenet that plants should be grown without any synthetic fertilizer or fossil fuel. These flawed tenets are directly related to each other. In other words, reliance on exploiting animals is precisely what allows advocates of “natural” farming to justify avoiding synthetic fertilizer or the natural gas used to produce food. Take animals out of the agrarian equation and you have to acquire soil fertility in other ways. So, how does the ethical vegan respond to this quandary?

I’m becoming well aware of veganic agriculture. And I have hope for veganic agriculture. I imagine that-though technological progress-we may one day be able to create a global plant-based agricultural system using green manure and other non-synthetic enhancements. For now, though, my response cannot be so idealistic: if we want to take animals out of agriculture, we’re going to need to use fossil fuel and synthetic fertilizers-and even some level of pesticides and fungicides-to feed billions of people a plant-based diet devoid of intentional animal exploitation. I realize that this assessment might not sit well with many vegan advocates-who tend to be environmental advocates as well as animal advocates-but keep two things in mind: a) manipulating the environment to make it feed billions of people will always come at some cost (people who talk about a “free lunch” in agriculture-ahem, Pollan-are dreaming), and b) there are, with technology, remarkably encouraging ways to minimize the impact of these necessary synthetic inputs.

So here are a few reasons why I think it’s possible-and desirable-to remove animals from agriculture, produce enough food to feed 9 billion people, use fossil fuels and other synthetic inputs, and still have an environmentally responsible agricultural system.

-The overwhelming source of fossil fuel consumption in agriculture today is animal based agriculture. All that corn and soy is mainly the problem. Switching to a diverse agricultural system that produces plants for people to eat would dramatically reduce the need for fertilizer and fossil fuel, to the point that the environmental impact would be greatly minimized. Again, to think that any system of agricultural production in the modern world can break even in terms of energy costs is crazy talk. Holistic/sustainable advocates fail to calculate the energy wasted and required to remove an animal from a holistic system prematurely, not to mention killing, commodifying, and replacing her. As the World Preservation Institute reported late last year: a global vegan diet would reduce greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture by 94 percent. What more needs to be said?

-High end synthetic fertilizers can be extremely efficient when it comes to plant nutrient uptake-often more efficient than manure. In fact, customized fertilizers deliver more nutrients more efficiently than manure, which-not being in any way designed for the specific nutrient needs of the crop-has high rates of nutrient run off. Plant biologists have made great strides in matching crop nutrient needs with specific fertilizer profiles-but, they’ve only done this with corn and soy. What if we did it for 500 edible plant crops and grew them all in the United States? “That’s not natural,” the sustainable agrarians would say. To which I would respond: “Agriculture is not natural by your definition. Get over it.” Subsidizing the judicious use of these fertilizers makes more sense than subsidizing corn and soy production. The use of efficient, high grade, low run-off fertilizer could-calorie per calorie-be more environmentally sound than using loads and loads of composted manure or relying on rotational grazing.

-A plant-based system that eliminated animals would require much less agricultural space, an acute factor given the press on limited arable land globally. Rotational grazing gets people excited because it’s so “natural,” but there’s nothing terribly natural about chopping down rainforests to clear land so we can fatten animals and grow crops “holistically.” The only viable objection I ever get to this claim suggests that, under holistic systems, we would not need as much land because people would eat less meat. But this objections fails on at least two grounds. First, it’s naive to think that consumers are going to switch to more expensive animal product options so long as cheaper ones are available-and cheapness comes from industrialization. Two, and relatedly, eating limited animal products produced in holistic systems will become the domain of the elite. I see no reason to reform a food system so that wealthy people are the only ones able to eat in a way that supposedly respects the environment and the welfare of animals.

-Finally, advocates of sustainable agriculture support the holistic model because it theoretically eliminates dependence on fossil fuels. While I’ve already mentioned many problems with this goal, there is one that I haven’t mentioned that’s more important than all put together: the worth of an animal’s life should never be measured in barrels of oil.

Yesterday I left off with the idea that the barriers to animal liberation are so deeply entrenched that only the most systematic kind of thinking about the roots of hierarchy, privilege, and domination can begin to take them down. The following piece, which is long but well worth reading in full, is exactly the kind of thinking I had in mind.

-JM

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s Rape Rack by Carolyn Zaikowski

The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for white, or women created for men.-Alice Walker

Feminists and animal rights activists don’t want to talk about it, but they have a lot in common. They don’t want to hear about it, but they need one another to move forward. Being a feminist and an animal rights activist gives me an interesting perspective. I have managed to straddle both movements and witness this fantastic resistance that each side has to the other. This resistance becomes deeply painful when you’re standing in the middle, attempting to be a bridge, watching so much revolutionary potential fall through that stubborn chasm.

Most feminists have been pretty good at asking hard questions. We demand that male privilege, white privilege, able-bodied privilege, heterosexual privilege, Euro-American privilege, class privilege, and many other privileges be analyzed. Some of us have addressed these questions about privilege better than others but, generally, serious feminists have gotten to the point where we recognize that the movement is not simply about gender. Women’s lived experiences stretch across multicolored, multitextured layers of identity, culture, history, and context. In order for feminism to be truly relevant, then, it needs to examine all of society’s power structures. If it doesn’t, it will apply only to rich white women who are not negatively affected by hierarchical orders of race, class, and nation, to name a few. In its most revolutionary form, feminism is a movement that seeks the dismantling of domination itself and all of the frameworks which allow it.

So it worries me that hardly any feminists have questioned one of our most fundamental expressions of power and domination: human privilege. It worries me that so few feminists have examined how this particular aspect of experience shapes our beliefs and actions on virtually every level, just like all other aspects of identity do. It worries me that so many feminists have overlooked the fact that determining one’s inherent worth based on their membership in a species is just as arbitrary as determining one’s inherent worth based on their race, gender, body size, sexuality, national origin, or any other identity marker. It worries me that feminists have overlooked the reality that human privilege is an analogue to all other privileges. It worries me that all of the same mechanisms which have been used to justify and enable violence against human groups have also been used to oppress nonhuman groups. It worries me that human privilege is indelibly connected to violence and misogyny in a tangled web of hierarchies and binaries, and that feminism, with its revolutionary potential, with its uninhibited call to justice, has generally been silent about all of this.

I want to ask the animal questions. Keep in mind, they are not unreasonable questions. We have asked similar questions about race, class, and nationality. We’ve done a similar analysis of many other power structures. We have recognized the complex, intersecting configurations of experience which allow so many oppressions at so many junctures. Yet most of us stop when nonhumans appear at such junctures. Even though examining the domination of nonhumans is nothing but a logical extension of feminism, even though this is the place feminism almost arrives at so often, virtually all feminisms have sidestepped when the next logical question would have been, what about animals?

When we get to places where animal questions might arise, we turn away. We lock up our wellsprings of inquiry and empathy. We don’t ask about how billions of nonhumans fit into webs of power and violence. We don’t want to know how nonhumans fit into this capitalist, patriarchal, racist, hierarchical scheme that has reached deeply into so many of us, in so many different ways. We challenge the false dichotomy of masculine/feminine but put so much faith in the false dichotomy of animal/human. It doesn’t occur to us that human privilege may not be any more “natural” than male or white privilege– that the human/animal dichotomy is just one more socially constructed method of organizing power. In an arbitrary and illogical swipe of its arm, feminism has reserved for human groups its important insights about social constructions of power and identity. Conceptually, feminism has written nonhuman animals out. It has erased them using mechanisms that are alarmingly similar to the ones men have used to erase women.

I want to delve deeper into the animal questions, but first I have to ask you to put down your defenses. The answers to the animal questions involve things as intimate as what or who we put into our mouths, chew, taste, enjoy, swallow, digest, and eventually shit out. The answers to such questions can bring on powerful and painful psychological, emotional, and physical reactions; reactions which all too often make us shut down and become defensive. The answers present virulent contradictions in our worldviews and require lifestyle changes. The answers often highlight our complicity in massive, institutionalized violence. Unthinkable, unspeakable violence.

But I want to push feminism into that profoundly uncomfortable space, and I don’t think feminism can move forward without going there. I believe that the future of feminism lies there, in that hardest, darkest space of so many nonhuman animals’ experiences. If we go into this place, we will start to understand the workings of the basest domination.

There are times when black activists have to push whites into a similar space. There are times when “Third World” feminists have to push “First World” feminists into such a space. All the time, gay activists have to push heterosexual people into it. It is a space in which violent power imbalances are confronted by those who abuse their power. There are times when women have to push men into that uncomfortable space, a place in which there are two choices: look away from male privilege, or look it in the face and see the unbelievable pain it has caused. And there were times when all of these confrontations seemed just as inconceivable as the one in question. But pushing these comfort zones is the only way in which change has ever occurred or will occur.

Who is going to push humans into that hard space?

The answer is, unless nonhumans figure out a way to revolt, we are going to have to push each other into it. And even though facing our domination of nonhumans is an incredibly painful process, there is no justification for it not being done. The brilliant, important work we do for humans does not give us a free moral ride, a free pass to be violent toward nonhumans. So when you come upon this space, what will you do? Will you look away from human privilege, or will you look it in the face to see all of the unbelievable pain it has caused?

I want to push feminism into the space where it examines the consequences of human privilege. It will not be easy, but in this place we can examine how we have taken on the eyes, the actions, the beliefs of the oppressor. In this place we can see that we have used all of his tools. That we are complicit in the vile, unthinkable acts of physical and sexual violence toward nonhuman animals which are happening literally every moment. That we are using the master’s tools not to dismantle his house, but to help the master oppress those in his darkest hidden dungeons.

I invite you to come with me to this frightening space. To do so you will have to fight your will to defend and deny human privilege in the same way that men defend and deny male privilege. You will have to exchange your defenses for the deepest empathy imaginable. You will have to take the energy of those defenses and turn it toward your desire for change. To come with me, you must agree to witness beings the way you have wanted to be witnessed. To believe that their pain is as real as yours is. To feel their yearning for liberation the way you feel your own. I want you to look into this space with me, and I want you to make a choice about what you are going to see and what you are going to do about it. I want all of us, together, to use our feminist eyes to compassionately witness the suffering of nonhuman creatures.

~

Open the door. This is a violent space.

It is a frightening space, a space which throbs like a heart, a heart that is shattered but still alive. It is the master’s secret basement. Eyes look out at you from its darkest corners, terrified of you because you are a human. There are so many questions in this space which need to be asked. Look in. Find him. Find pieces of him in yourself. Ask the questions, even if they do not have answers. Create the conceptual realm.

Ask the master: Why are ninety percent of sport hunters men? I want to know why; I want to know what justifies this absurd “masculine” delight in killing beautiful creatures. These creatures, they are the defenseless prey of men just like I have at times felt like the defenseless prey of men. So often, I feel hunted, I walk down the street with the male gaze gauging me like a gun. I understand the deer’s predicament, her fear of men, I even understand her fear or me, her terrified eyes. It comes from the exact same place that my own fear comes from. After all, ninety percent of the hunters of women are also men.

Let’s walk in a little further to this nightmarish cellar. Let’s really try to see the world through the eyes of others. Let’s be brave.

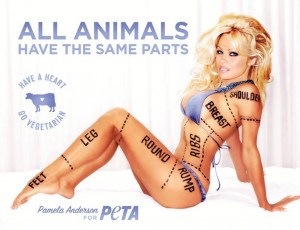

Ask: Why do meat and masculinity have such a long, complicated history of symbolizing and constructing one another? Need I list off all of the meat-related euphemisms for penis and penis-related activities? Sausage, say it without laughing. Sausage. Beat that meat. Choke that chicken. Your meat is your manhood. Real men eat steak. Real men cook on the grill. Real men have meat on their bones. You’re never going to be strong if you don’t eat meat, and real men are strong. Real men play football. Vegetarians are fags. Vegetarians are pussies, faggots. Girls. And girls are like vegetables, passive and weak.

Ask: Why do you feel like a piece meat after being violated or objectified? Hear the master shouting from the darkness: Leg of lamb! Chicken breast! Let’s order some legs and breasts! He fucked her like she was a goddamn piece of meat and she loved it! He fucked her with his meat! With his sausage! With his wiener! She wanted it! Bag her face, man! She’s pretty hot when you don‘t look at her face! She’s got nice tits! We are pieces. We are fragments. I love legs and breasts! Legs and breasts! Legs and breasts! I’m a real leg man! What about you? You seem like a breast man! Can I get a bite of that thigh? Thanks man! Ask him whether or not he’s talking about you or his meal. Maybe he’ll tell you he’s talking about both. After all, women and animals are consumed together. Made into meat and pieces, into pieces of meat, together. These are metaphors for our oppression. Animal bodies are the reality behind our metaphors. All of us know the reality of the sheer horror of animals’ lives on some level, which is why we don’t want to be treated like them.

Ask him, this master who has for so long held the pens: Why are there so many more animal words in that insult or objectify women than men? Ask: Why we are called bitches? Yes, ask this question and maybe he will remind you that, like the female breeding dog who struggles against being forced to have sex with the male breeding dog, we are difficult. Ornery. Angry. We are bitches who don’t want to be fucked. We are fat cows; we are hot young chicks; we are obnoxious old henpeckers. We are sex kittens, foxy ladies, evil vixens; we are mindless social butterflies. We have beavers. We have pussies. We don’t like to be treated like animals. Pens are power.

This space is enormous. It creates a bridge across thousands of years.

Ask him: Why was it that the men who dominated science started the practice of cutting apart live animals? The maps of science weren’t written by the oppressed. Would we have defined animals differently? Why don’t we redefine them, now that we have a stronger say? We, who have always known how it feels to merely be another’s goal? We, who have been raped by our fathers and brothers and partners and husbands and friends, prodded in secret places by doctors, sterilized without our consent? We, who, as men vivisected our nonhuman sisters and brothers, were being burned at the stake, pathologized, and lobotomized by those same exact men? What about those of us, largely people of color, who have been dissected by scientists right alongside nonhuman animals, who have been literal slaves on farms beside animals? We, who, together with an animal, destroyed Eden, and together were blamed for all of the evil in the world? But we always forget how we had company that day, how our dual fates were sealed on that page by the Father. We want to forget the destiny we shared with the snake in our most significant cultural myth.

Ask him: Would women have seen nonhumans as having inherent worth, worth beyond their use to humans, had we been the ones who set the standards? Held the pens? Made the maps? Written the textbooks? Founded the universities? Told the cultural myths? You do realize that this idea about nonhuman animals not having inherent worth was originated by men, right? One which we bought into for some reason? You do realize that these ideas about animals were specifically written out and articulated by the great male philosophers and the notorious schools of patriarchal “morality” so often ridiculed by feminists– Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Christianity, ad nauseum? How have we overlooked that common framework? Look at it. Stare at its violent, vile, disgusting face.

Ask: Why is it that abusive men regularly involve companion animals in woman battering? And why is this the aspect of domestic abuse that is the least recorded at police stations and shelters, even though it happens all the time? Can I ask, as I sit in this violent conceptual space, why it is that men are more likely than women to engage in violence in the home against the women, children, and companion animals who make up families?

Ask this master, as we walk through these deepest catacombs of pain: Why, for centuries, have men dominated both women and animals by domesticating them? By owning them? By consuming them? Ask the master, why these connections between animal husbandry and being a husband?

Why have powerful men co-opted the control of both women’s and animal’s reproductive systems? Ask the piece of the master that is in you: Why do women go along with this twisted scheme? Why do we drink the stolen milk of females in factory farms? How do we bear to know that their lives are defined specifically around their breasts being hooked up to machines or prodded and squeezed every day on “humane” farms? That they live attached to these tit-sucking machines and hands, often given horrible drugs so that they will keep producing for the master and his cohorts? That these drugs in our food give us reproductive cancers in turn?

And how can we eat the coerced eggs of females? The females who are supposed to spread their wings, go outside, live freely but instead inhabit tiny cages where their feet grow around feces-covered wires? Where from sheer madness they peck one another’s eyes out with the remains of their seared-off beaks? Even on “humane” farms, billions of females have been designed–literally, over centuries of breeding–to fulfill the sole purpose of being egg machines. Do we truly consent to such a world? That milk isn’t ours. Those eggs aren’t ours. Those bodies aren’t ours. Meat and dairy are the opposite of consent.

How do we allow the babies of mothers to be stolen? Have you ever seen cows mourn the loss of their calves? It’s phenomenal. Have you heard the bovine mothers cry? You would have thought they were human. Or maybe you might have been reminded that you are an animal. Have you ever seen the enormous, beautiful pigs– animals who are more intelligent than dogs– go mad sitting in their shit and piss, throwing their largest bodies against the walls of their tiniest death-laden pens, ripping their mouths apart as they try to bite through the metal bars? Have you ever seen their babies suck on their breasts through those prison bars or read stories about how these creatures frequently jump fences and the like in escape attempts? Have you ever realized that the animal farming is the most large-scale, institutionalized control of female reproduction, sex, and bodies-in-general that has ever existed?

Let us never forget the male bodies victimized by this patriarchal space. The useless young male chicks are thrown away alive in dumpsters or turned into veal. And the bulls become eunuchs, honorary females, having their testicles burned off with hot irons. Any bull who dares run away from even the most “humane” farm will be stun-gunned and wrestled back into life-long captivity until slaughtered for his body when his reproductive mechanisms become useless.

And here’s the big question. The question I don’t really want to ask because it makes me wince, it makes my skin crawl and fills my heart with horror. This is the topic which gets me in trouble with both feminists and with the master, again and again, perhaps because it makes so clear the ultimate thing we are not supposed to notice, this horrendous interconnection of oppressions: Did you know that many farmers nickname that place where our nonhuman sisters are artificially inseminated “the rape rack”?

The rape rack.

They actually call it the rape rack. This is not a term I constructed to be shocking. This term comes from our collective psyche and the psyches of farmers. And some version of this device, no matter what it is called, is central to all animal farming, whether permaculture or factory farms, local or distant, “humane” or otherwise.

Here is where my mind starts to shut down because I become so horrified at the implications. How do we bear to live in a world in which conditions exist so that anything, anywhere, no matter who was hooked up to it, could ever, even by the smallest stretch of imagination, be called a rape rack?

Feminist visions cannot come true in a world where rape racks exist. A feminist world cannot be a world where anyone, any life, human or nonhuman, male or female, black or white, two legs or four, could ever be defined solely based on their relationship to such a paradigm. A feminist world cannot be one in which anyone is defined based on how many times they can be inseminated, give birth, have their children stolen from them, drugged, be hooked up to a breast-sucking machine or have their breasts kneeded, sometimes daily, by humans who make money on their milk, have their milk and eggs stolen from them, and then be sent back to the rape rack or, in more “humane” situations, the insemination rod that gets pushed into their vaginas. As long as the rape rack exists, we will live in a world of rapists.

It’s hard for me to go here and feel the enormity of this. How hard is it, then, I wonder, for those who don’t want to see the oppression of animals for what it is? For those who don’t want to analyze human privilege or believe in this power dynamic? For those who refuse to acknowledge this dungeon? When I think of it all, my mind starts to writhe with the pain, the pain of wanting to save them and knowing I cannot. There are billions of nonhuman animals who live these unbelievable lives– literally billions. Tens of billions in one year in United States agriculture alone. That is a number so large I cannot even fathom it. That is billions more than the entire human population, in one year alone. That does not even take into account sea animals, the millions in vivisection and dissection, the millions who are tortured in fur traps and go mad in fur farms, the millions who are turned into leather shoes, the millions of companion animals who are abused, the millions of unwitting nonhumans who are hunted down for no reason with men’s big guns, the millions of nonhumans who are murdered during men’s big wars, with patriarchy’s big phallic bombs.

I feel the siren song of denial tugging at me: Do you feel it, too? This makes sense. The implications are too unfathomable. Animal rights activists often say that their introduction to the reality of animal lives was like taking the Matrix’s red pill. You cannot go back. Opening to the true lives of animals changes one’s entire paradigm so that you almost cannot see anything the same way. You begin to see that our entire civilization is based, in one way or another, whether literally or metaphorically, on the mass, unnecessary, institutionalized destruction of fellow beings. This is a world-view a person can’t understand unless they have truly gone there. I, too, even as a long-term vegan activist, often feel the need to walk away from this horror, to stop attempting to create a language which does it justice. But then I remind myself that this intoxicating song of denial is a trap. I remind myself that it wants me to justify or downplay the violence, to unfeel the horror of this space, to unsee what I know to be real, solely in an effort to protect my conscience. The blue pill is comfortable but it’s truly nothing more than a dream.

We love animals. We do not want them to suffer. We are friends with animals. We spend our lives alongside cats and dogs, fish and rabbits, birds, squirrels. We grow up collecting teddy bears and watching cartoon mice. As small children, we are often horrified when we find out what meat is, only to be confronted by a society in which such a horror is unacceptable and parents who refuse to let their children become vegetarians. Just like other groups at other times have done, we stay complicit in this violence by shutting off when the burden of pain is too large, when the connections feel too real and the aura of helplessness too overwhelming. We go inwards. We deny and justify and rationalize and intellectualize and become fragmented. In panic and numbness we use our privilege to make arbitrary, unconscious decisions about who should live and who should not.

We stay complicit by smothering portions of our hearts that want to care, by disallowing the life-oxygen of empathy to extend properly. But hearts were not meant to be smothered in this way. Hearts become dysfunctional when they are not available in their entirety, just like bodies with broken legs do. So why do we push the nonhumans away, into that special, shadowy section of our hearts? Why do we collude with the master in maintaining this dark, horrible, soundproof basement of colossal pain when we could be knocking down the walls?

We are animalized and they are feminized in complicated rings of domination and control and coercion and abuse and domestication and alienation. We do not need to be scared of these comparisons. To extend empathy beyond humans does not mean trading the human struggle for the nonhuman struggle. It means that both struggles will attain a new depth, one we could not conceive of before. It means putting one more hole in the stubborn cycle of violence. There is simply no need to keep justice all for ourselves. Empathy is not in limited supply; rather, it is like a muscle which gets stronger and larger with use.

Sit back. Take it all in. Before leaving this place, allow yourself to wonder. Allow yourself to remember your incredible power. Allow yourself to envision a world in which there is no unnecessary domination of any animal, human or nonhuman.

~

Ultimately, we, as feminists, have to do some serious soul-searching about all of this. We have to earnestly consider whether it is fair of us to ask the world to witness our voices and our pain when we so often refuse to witness the voices and pain of others. At its deepest level, is feminism being honest if it does not engage in this witnessing? I’m not so sure. Is it fair for us to call for our own dominators to stop, while simultaneously being dominators of billions of others? I don’t think it is. Is it fair to expect that those who oppress us examine their privilege, even though we do not examine one of our most fundamental privileges? Is it fair to demand autonomy, while simultaneously defining animals only in terms of their use to us? Does any group have a right to demand freedom while systematically keeping another group unfree?

I don’t think that a revolution in feminism can happen while feminists themselves are still colluding with this patriarchy-defined framework of dominator-dominated, and when those in question are arguably the most helpless, outcast, and unheard of all. No, I don’t think a feminist revolution can happen while this paradigm, while this bottom line, is still with us, and we are not taking accountability for our role in it. I want a world in which there is no domination. I want a feminism that recognizes all hierarchical power arrangements and seeks to eliminate them. I don’t think this request is unreasonable. In fact, I think it is one of the most reasonable requests ever made, and I think it is the largest, most profound and authentic expression of feminism possible.

This is a call to honestly ask ourselves, a call to be brave: With what eyes do we look at animals? Do we look at animals with feminist eyes, or do we look at them with the eyes of the master, those eyes that believe in the rightness and naturalness of domination? Do we look at them with indifferent, entitled, or domineering eyes, the same kinds of eyes that have oppressed us? Or do we look at them with revolutionary eyes? This question is crucial to the future of feminism. If we continue to look at this entirely silenced, universally subjugated group with the eyes of the old paradigm, a feminist world will not be realized, because feminism’s feet will still be caught in that violent framework of human and male domination. Feminism’s hands will still be bound to the master’s rape rack.

Animals are the ultimate, the fundamental Other. Let’s make the connection.

Sometimes I think the human-animal relationship would be much better off if humans didn’t think so damn much. At the same time, I think the human-animal relationship would be much better off if we were just a bit more thoughtful. Either way, it’s amazing how easily the forces of denial and willful ignorance are deployed to justify the pleasures of the palate and powers of exploitation.

For those willing to confront the ethics of eating animals, what often happens is this: our super-charged, overpowered, hyperactive brains enable us to think ourselves out of making the right choice (just read the recent finalists in the NY Times Magazine ethics of eating meat contest). A classic example of this regrettable ability to intellectually evade the truth about animals involves the way many people respond to the question of animal emotions. When we observe what appear to be genuine expressions of animal emotion, many of us actively and almost instinctively rationalize them away. It’s a preprogrammed response, we say. We’ve no way of really knowing what another species is feeling, we say. There’s no hard data, we say. We say these things, I suppose, because we’re complicit. We don’t want to stop benefitting from exploitation, but I imagine we can think away that fact as well. The human mind is a fickle little machine.

These ideas and standards of truth aren’t the yammering of wingnuts. They’re routinely promoted by professional philosophers and animal scientists. Nevertheless, lacking such authority, I feel safe in saying that to deny animal emotion is patently absurd. It ignores the situational ingenuity that we’ve seen all kinds of animals repeatedly demonstrate. It succumbs to a speciesist interpretation of thought and feeling, thereby confirming the human predilection for prejudice. Put simply, to deny animal emotion is to ignore the obvious. So many aspects of life are so maddeningly complicated. But not this issue. This one is simple. So simple.

I recently read a story about a mother dairy cow who gave birth to twins in a pasture. It was her fifth birth as a result of being repeatedly artificially inseminated. This time, with twins, the mother cow saw a chance to rebel. She hid one of the twins in the pasture, led the other to the barn (as she’d done with her five previous children), and saved her milk for her hidden calf out in the field. Is it in any way viable to say that this mother lacked recognizable emotions? I don’t need an expert to answer this question.

Sad thing is, most people, often very smart people, don’t think about the implications of this story at all. I’m constantly rattling on to colleagues, friends, family about these stark examples of animal emotionalism. The general reaction is to say “wow” or “how sweet” and then willfully fail to connect the dots. How is it that direct and quite powerful evidence of animal emotion can exist so independently of our everyday behavior? I’d argue it’s because we’re so deeply trapped in customary habits-habits that conform perfectly with the most basic cultural assumptions-that the grotesque barriers preventing connections seem to be as normal as the air we breath and the water we drink. Admittedly, it’s jarring to realize, as a thinking and caring person, that-when it comes to something as fundamental as our connection to non-human life-we’ve had it all wrong. Or worse, that we’ve been blissfully complicit in massive suffering.

More astute critics argue that, in order to tear down these contemporary barriers, we have to “strike at their roots.” We have to confront nothing less than the origins of hierarchy and exploitation in order to rebuild a cultural context that makes animal liberation a no-brainer. Tomorrow, I’ll be putting up a guest post by Carolyn Zaikowski, who is working to do exactly this. Her thoughts on striking at the roots are some of the smartest and best articulated I’ve read in a long time.

Stay tuned. Subscribe. Go Vegan.

I’ve been resisting this post for a while. However, after about the tenth observation that many of my posted images of animal slaughter resembled images from Abu Ghraib, I decided that the post-dreadful as it would be to do- had to be done. Please note: I’m not suggesting that killing/abusing a human and killing/abusing an animal are morally equivalent actions. That is NOT the message these graphic juxtapositions are intended to convey, or the issue I’m hoping to raise here.

What these parallels between animal slaughterers and the Abu Ghraib torturers do point to is the insidious nature of dominance-be it human over human or human over animal. There’s something about unchecked human control that tilts all too easily toward abuse, brutality and, worse, the gut-wrenching celebration of these qualities. As readers know, I do not place these horrific images on my site casually. In no way am I intending to be sensational.

But the fact is that these images are real. They tell us important, if disturbing, things about the darker side of human nature, a side manifested all too easily in control over the most vulnerable- humans as well as non-humans. On a final note, it’s worth mentioning that, as I arranged this macabre collage, I found myself as disturbed and saddened by the animal images as I did the Abu Ghraib ones. I think it’s the celebration of violence-or at least indifference to it- that really sank my spirit. It was the happiness of it all that clarified for me how easily we dehumanize ourselves under the influence of objectification.

![chipotle_billboard[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/chipotle_billboard1-300x190.jpg)

![cow-and-calf[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/cow-and-calf1-300x225.jpg)

![AbuGhraibScandalGraner551[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/AbuGhraibScandalGraner5511-234x300.jpg)

![Slaughter_Pic[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Slaughter_Pic11-179x300.jpg)

![abu-ghraib-leash-715453[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/abu-ghraib-leash-71545311-300x255.jpg)

![Daisyintothebarn[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Daisyintothebarn11-300x225.jpg)

![x130165091301713635_7[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/x130165091301713635_711-300x198.jpg)

![IMG_0017good[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/IMG_0017good1-300x228.jpg)

![abu-ghraib-torture-06[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/abu-ghraib-torture-0611-300x240.jpg)

![e80e4266-1c4e-4033-a851-dbcf73c08bdd[1]](wp-content/uploads/2012/05/e80e4266-1c4e-4033-a851-dbcf73c08bdd11-300x225.jpg)